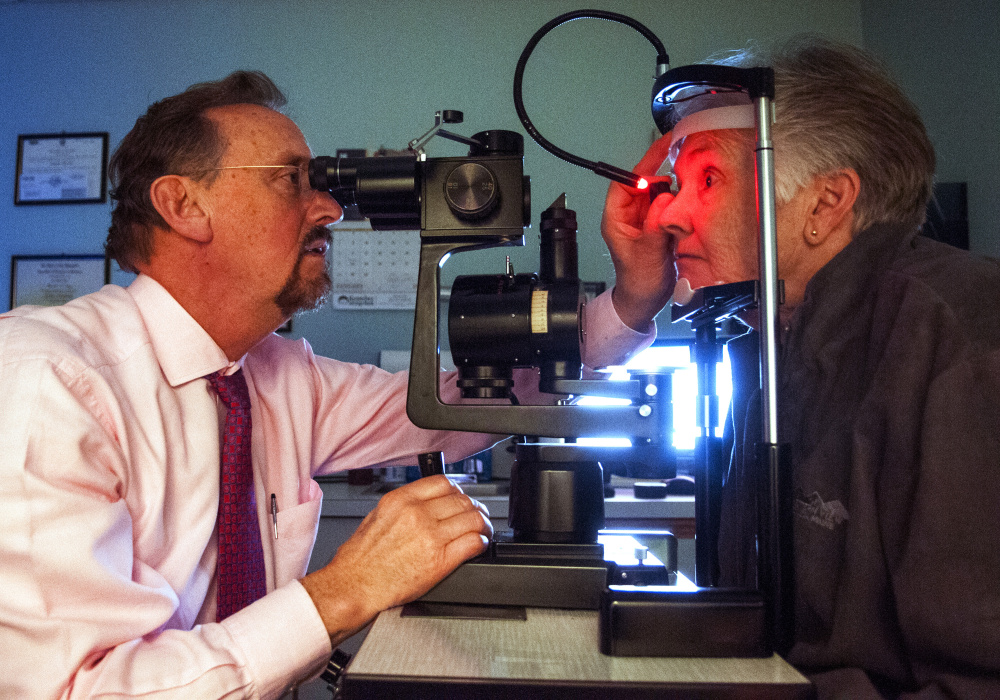

After seeing patients at his offices in Hallowell and Winthrop for the last 40 years, family eye doctor Kenneth Nuzzo will retire later this year.

The move is partly because Nuzzo has reached retirement age — he’s 70 this year. But it’s also due to changes in the health care industry over the last 20 years that have made the day-to-day running of his practice more time consuming and costly.

“I would continue to do this, but it’s just become too burdensome,” said Nuzzo, who runs the business with his wife, Eileen, and three other employees.

Nuzzo, an optometrist, closed his Winthrop office at the end of December and will be seeing patients in Hallowell until March. Eileen said they are in talks with established practices about the possibility of selling the business, which sees about 20 patients a day.

Both Nuzzo and his wife said they have enjoyed running their practice and helping patients with their vision needs. But they also said that changes in the health insurance marketplace, federal privacy laws and the increasing need for doctors to store data electronically — among other changes — have made it harder and costlier for them to focus on their patients.

A typical visit to Nuzzo’s office these days isn’t what it was 20 years ago.

In 1995, a patient visiting Nuzzo with an eye complaint probably would have paid cash, he said. Then Nuzzo might have taken her history and performed some tests. If he suspected the patient had glaucoma, for example, he would test her optic nerve for damage. If the results looked strange, he might have then performed more tests during the same visit.

But now, with most patients using health insurance, staff must first make sure their policies will pay for the work. Then a technician will perform tests on the patient before Nuzzo sees them. If he believes more tests are required, the patient may have to return for a separate appointment, because policies that are meant to prevent insurance fraud limit the number of tests that can be ordered in one visit.

While many of those new requirements are well intentioned and may lead to a better health care system, Nuzzo said, they make it harder for doctors like him to remain in private practice and more inconvenient for patients.

“You can’t do it alone anymore, not and do it well anyway, or successfully,” Nuzzo said. “There is too much paperwork involved and too many outside entities that are constantly breathing down your neck. They’ll change regulations in a big way a lot of times so you have to keep up with that.”

Besides all the paperwork, Eileen Nuzzo, who manages the business and handles its books, also said that dealing with insurance companies has become increasingly difficult. Because the companies don’t reimburse the full amount for the services they provide, she said, they sometimes have to write off the extra costs.

Given the challenges facing independent providers, Nuzzo said, he and several other central Maine eye doctors even considered joining forces a few years ago, but that effort didn’t pan out.

The challenges facing the Nuzzos are related to those facing small, private practices in other fields of medicine.

Many solo practice health care providers have faced increasing pressure to join larger practices or systems, according to Gordon Smith, executive director of the Maine Medical Association — which represents physicians, not optometrists.

“People (are) fleeing private practice” to work in hospitals or health centers, Smith said. “The cards are stacked quite deeply against solo, small practices.”

While solo practitioners have more independence, Smith said, insurance programs tend to provide less reimbursement to them than to larger health care providers. It’s also harder for solo practices to install costly electronic medical record systems, Smith said.

Nationwide, just over half of the optometrists who responded to a 2014 survey by the American Optometric Association said they had an ownership stake in a private eye care practice. About 70 percent of those respondents were age 40 or older.

The president of the Maine Optometric Association, James Patrick Smith, said he thinks most Maine optometrists are in private practice.

While Smith said it can be difficult for younger optometrists saddled with student loan debt to buy into a practice, he added that the number of people graduating from optometry programs nationwide is increasing, and there is demand for their services in places like central Maine.

Smith also said that Nuzzo will be missed by his peers.

“I’ve known Ken for a long time,” Smith said. “I’ve known him to be a real pillar of the optometry community, both locally and statewide, for the community and for his patients. He will be sorely missed.”

Nuzzo said that he has often tried to focus on his patients.

In 2015, the federal Medicare program began reducing its payments to health care providers who had not installed an electronic health record system and begun following a set of practices to use it.

The Nuzzos installed their electronic system about five years earlier at a cost of roughly $65,000. They also hired an employee to type information into the system during each visit, rather than having Nuzzo split his time between a patient and a computer. Though that added to their business costs, Nuzzo said he preferred not having to keep looking back at a computer.

“In the end, that’s probably good that you have to (have electronic records), but it’s time consuming,” Nuzzo said. “If you want to put in 40 hours a week, you’re going to have to apply a large percentage of that to administration, which isn’t doing you any good. If you come in with something in your eye, the fact that I spent two hours on administration isn’t going to make you feel any better. They’re not going to feel better until we actually get in there and start digging.”

The Nuzzos have also felt burdened by two other federal regulations, a privacy law passed by Congress in 1996 and the Affordable Care Act, aka Obamacare, which President Donald Trump and other Republicans have said they want to repeal and replace.

As Nuzzo prepares to close his Hallowell shop, several longtime patients said they’ll miss the quality of care he provided for them and the welcoming atmosphere in his office — as well as his knack for jokes.

“He makes you feel at ease,” said Julie Bernier, a 71-year-old Augusta woman who was having her yearly check-up last week. “He’s a pretty easy-going guy. In another life, he could have been a stand-up comedian.”

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Send questions/comments to the editors.