By Amy Driscoll

The Miami Herald

On her 7th birthday, when her father makes the agonizing decision to give her away to the local fabric vendor, who can offer a better life, Claire Limye Lanme Faustin vanishes.

One minute she’s there — a limber figure in a pink birthday dress walking toward her father’s shack in a Haitian fishing village to gather her school uniforms and notebooks for her new home — and then she’s gone.

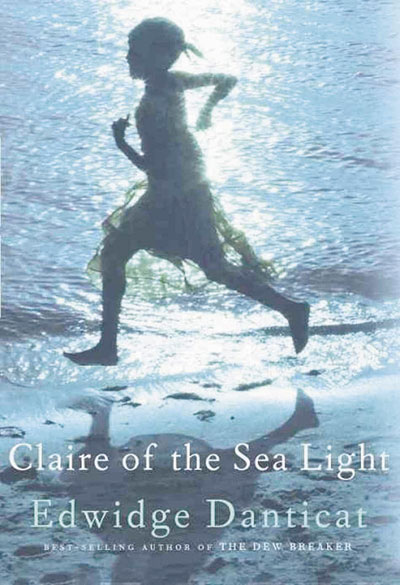

In Edwidge Danticat’s luminous new novel, the ensuing search for the missing girl serves as a way of re-examining what we overlook and undervalue in life. Set on a single day in tiny Ville Rose, Danticat tells the story through a kaleidoscope of perspectives that illuminate life in the island nation where the roles of ex-pats, gangs, radio journalists and shopkeepers crisscross the decimated landscape.

In a voice tuned to the frequency of sorrow, with a calmness that neither apologizes nor inflames, the Miami-based author lays out the terrible choice that many in Haiti have faced: Keep a child in deepest poverty or offer the child to someone with better prospects.

Danticat, who was born in Haiti and has lived in the United States since childhood, has been successfully serving as interpreter between the two worlds for years. In “Claire of the Sea Light,” Danticat, winner of a MacArthur fellowship and an Oprah Book Club author, builds on her previous work conveying the intimacies of daily Haitian life while also keeping enough distance to make sense to an audience far from the violent coups, earthquakes and destitution that have marked country’s difficult history.

And although the story’s timeline may be a touch disorienting at the start, it quickly straightens out into a remarkably well-plotted combination of mystery and social critique.

Danticat is a beautiful storyteller who doesn’t shy from the brutalities Haitians face: a radio reporter is executed in his bed, a gang leader sips a beer with a prosthetic arm. But she also applies a finely tuned sensibility to the beauty that surrounds the pain. Lips red as cherries, a talcum-powered neck, a white hibiscus tucked behind an ear, a wall of water that rises from the sea like a “giant blue-green tongue, trying, it seemed, to lick a pink sky” — all these images go into Danticat’s vision of Haitian life.

In the novel, the father, Nozias, a poor fisherman, has been raising Claire on his own since her beloved mother died in childbirth. Each year on the child’s birthday — the anniversary of her mother’s death — he takes the girl to visit the grave. And each year, he struggles with the idea of giving Claire to Madame Gaelle, a “woman of means” in the village who has lost her own child.

For six years, he turns away from the decision. But then Claire turns 7 and Gaelle, who nursed the child after her mother died, decrees: now or never. The adults make their deal. And the child slips away.

The search — up the hill to the lighthouse, along the beach where a fisherman has drowned in a freak wave — provides the vehicle to examine the lives of the perpetually unseen, the less-than, the lost.

They aren’t always the people you might expect.

Gaelle, for example, is far from the imperious figure in the gold evening dress that Nozias perceives. A widow, she’s actually impossibly lonely, mourning her own losses, trying to find a way forward, but keeping her struggle to herself.

And then there’s Louise, the well-known host of a radio show, Di Mwen, or Tell Me, who is marginalized in her private life by a longtime lover who never gave her his full attention or respect. When he rejects her, she finds unexpected liberation in the slap that ends the relationship.

A guest on Louise’s show, meanwhile, is reclaiming her own moment of invisibility. Flore used to be the maid in a rich man’s house until she was raped by the son. On the radio, she makes the attack public for the first time. But the rapist, Max Junior, is running from his own demons and has more in common with Flore than either of them thinks.

Finally, there’s Claire herself, whose small absence has triggered a wave of re-evaluation. In the final chapter of the book, we see the story through her eyes with an unexpected burst of clarity that wows the reader.

The day in Ville Rose comes to an end in much the same place where it started. But the village — and readers — are changed. Danticat’s determination to face both light and dark brings the story to life. But her skill as a writer makes the balancing act a pure pleasure to read.

Send questions/comments to the editors.