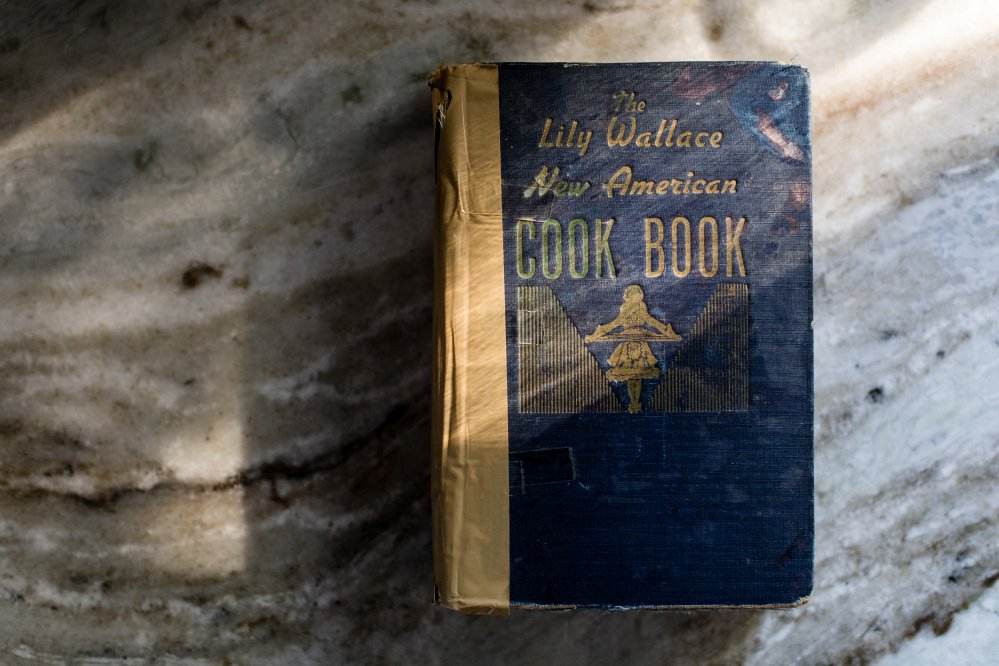

As I helped my 94-year-old grandmother clean out her kitchen before a move a few years back, she looked at a cupboard stuffed with cookbooks and suggested I take whichever I liked. My eyes flitted to her worn copy of Fannie Farmer’s “Boston Cooking School Cook Book” and a 1946 copy of the Lily Wallace “New American Cook Book,” its spine barely held together by packing tape.

But not these, Nana said, pulling those same volumes aside. “These are some of the oldest things I have.”

A few months later, my sister sheepishly told me that Nana had given the cookbooks to her, first thumbing through Wallace’s tome of numbered recipes to find one for Lemon Sponge Pudding (No. 2514) – a favorite, she had said. The page was dotted with stains and torn in places where drips of sugar had fused one sheet to the next. In the margin next to the pudding recipe was one tiny check mark: Make this one again.

My envy subsided when, a few months later, a package arrived from my sister with a beautifully framed, high-quality copy of the cookbook’s cover and the splattered page. The pudding wasn’t a dish made for special occasions, Nana told me later, and not necessarily one for company. She made it “now and then,” in rotation with Farmer’s baked custard, because she favored lemon.

Plus, she said, “the children liked it.”

Chelsea Conaboy squeezes a lemon with the help of her son, Hartley Byun. Photo by Yoon S. Byun

FOOD AS DIPLOMACY

The children. Five in all, four of them boys, and a husband with a career at the telephone company.

In the two years or so since Nana’s recipe went up on the wall of our kitchen in South Portland, I’ve begun raising my own two boys. I’ve thought so often about my grandmother, Margaret Conaboy, and other women of her generation, and of what childrearing was like in their households, often with bigger broods, less helpful partners, no daycare and more made from scratch – though less often done while balancing a full-time job as well.

Like other cookbook authors of the mid-20th century, Wallace argues for the importance of women’s work. As World War II was ending, women in many families returned from factories to domestic life, and they looked for ways to assert themselves in whatever venue they were allowed – a trend that had been building for decades – said Don Lindgren, an antiquarian cookbook expert and dealer at Rabelais in Biddeford.

Food is diplomacy, Wallace writes. It fuels family life and keeps people from “straying.” It has influenced all of recorded history, and it can dictate the future.

“[I]t is highly probable that the lives of children, whose grandparents may yet be unborn, will be influenced by the meals being served in many homes today,” writes Wallace in the introduction. (There is so little historical record of Wallace, beyond what she writes about her own life, that Lindgren wonders whether Lily Wallace may in fact have been a pseudonym.)

Encyclopedic cookbooks like hers – she claimed that 54 “leading authorities on domestic science and the art of modern cooking” assisted in writing it – were born from the home economics movement of the early 20th century and the practicality and accuracy that was important through the Great Depression and wartime. But they would soon fall out of favor in publishing, replaced by books filled with pictures or defined by big personalities, Lindgren said. Julia Child would change the nature of cookbook publishing 15 years later, with “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.”

Still, books like Wallace’s, tested and dependable, stayed on families’ shelves for years to come, sometimes standing in for distant family members, said Helen Zoe Veit, associate professor of history at Michigan State University, where she specializes in the history of food.

“You might turn to the cookbook as you might have turned to a mother or a grandmother living nearby and say, how do you do this? And you could turn to the cookbook, because the cookbook knew so much,” Veit said.

Chelsea Conaboy pours boiling water into a tray holding ramekins for Lemon Sponge Pudding. Her son, Hartley Byun, waits to taste-test. Photo by Yoon S. Byun

NO FLIPPING

Certainly, Wallace’s cookbook knew more than I did. For starters, I had no idea what a “pudding dish” was or even approximately what a sponge pudding should look like when finished. Short on time – see above, two young boys – and with my grandmother, now 97, living two time zones away, I consulted the modern-day cooking encyclopedia: the internet.

It led me astray.

Some sponge puddings apparently are meant to be flipped, being composed more of sponge than of pudding. Wallace didn’t call for flipping her pudding, but I thought perhaps that was one more thing she had assumed I would know.

When I flipped the mixing bowl I’d used as a stand-in for a pudding dish, a puddle of hot lemon goo oozed out onto my hand and the countertop. My 21/2-year-old son, Hartley, looked up at me with concern as I yelped in pain and then in frustration.

Two weeks later, we tried again, this time with ramekins. No flipping. Hartley helped juice the lemon and fold in stiff egg whites. Then we waited together for the pudding to bake.

Before my husband and I had children, life was marked by major milestones: a first job, then a new city and another, as I moved with my career. Next came a proposal, marriage, our first home. The markers that lie ahead seem different. They track the unfolding of a young life – two lives – and all of the daily tasks and rituals that, my grandmother knows well, make that unfolding possible, all of the things that create the splattered page of a family’s history.

Hartley and I ate the pudding together, sharing one dish and two spoons. We broke through the sponge top to a glossy yellow beneath and scraped at the bottom of the ramekin for every last bit.

Put a check mark next to this one, I thought. The children like it.

Chelsea Conaboy is a freelance writer and editor. She is the former features editor at the Press Herald. She can be contacted at: cconaboy@gmail.com; Twitter: @cconaboy

LEMON SPONGE PUDDING

The “New American Cook Book” called for using a pudding dish and cooking this recipe for 45 minutes. I don’t own a pudding dish and decided, as my grandmother often does, to use 4-inch ramekins and to reduce the cooking time slightly. I filled five ramekins for larger portions, though this recipe could be stretched to six dishes. I used the full amount of recommended sugar. Nana cuts it by a quarter cup.

Lemon sponge pudding made by Chelsea Conaboy. Photo by Yoon S. Byun

Serves 5 to 6

2 eggs, yolks and whites separated

1 cup sugar

1 tablespoon flour

Pinch of salt

1 cup milk

Rind and juice of 1 lemon

2 tablespoons butter

Preheat the oven to 350 F. Put a kettle of water on to boil to make a water bath.

Beat egg yolks. In a large mixing bowl, sift the sugar, flour and salt, and add to the egg yolks. Add the milk, lemon juice and rind, and beat thoroughly. Melt butter and add. In a separate bowl, beat egg whites until stiff. Fold the whites into the yolk and lemon mixture. Divide evenly into ramekins.

Pour boiling water in the bottom of a roasting pan. Place ramekins, evenly spaced, in the pan. Top off the water, if necessary (taking care not to get any in the pudding) so that the water reaches about halfway up the ramekins. Bake for 35-40 minutes, or until the tops of the puddings are very lightly browned. Chill and serve cold.

Send questions/comments to the editors.